Future Port of Rotterdam

Rotterdam, NL

| Type | Research |

| Year | 2022 |

| Location | Rotterdam, The Netherlands |

| Size | 13.000 ha |

| Client | Maritiem Museum Rotterdam |

| I.c.w. | Havenbedrijf Rotterdam |

| Team | Eric-Jan Pleijster, Artur Borejszo, Nerea Febré Diciena, Roberto Coccia, Martin Garcia Perez, Simon Verbeeck |

What does the Port of Rotterdam looks like in 2200? Nobody really knows, but we do know one thing: it will look significantly different from what it is now. That has everything to do with all the challenges and transitions that are on the table. Many of those are already happening right now! Perhaps the biggest challenge for the port is how to deal with sea level rise. Can the port use the 5 meter projected sea level rise in 2200 as a driver to a better port? The Port of Rotterdam recognizes the change that is going to come and seeks for ways to continue it’s ‘license to operate’.

Port on the move

The Port of Rotterdam has always been on the move. Always changing, never static. From the historical ports in early cities like Rotterdam, to the extensive industrial area that is it now, expanding from the historical parts of Rotterdam all the way into the North Sea. The landscape that once was part of a large estuary, is now the scenery for container ships, refineries and oil drums. A landscape of trade and transport, occupied by almost alien machines and otherworldly constructions.

Meanwhile the world is in a climate crisis, causing the sea level to rise. The sea level rise doesn’t come alone. It’s part of a complex set of challenges for the port itself and the city of Rotterdam: spatial challenges like salt intrusion, continuous sedimentation, soil subsidence, potential floods, severe droughts and the scarcity of fresh water. Moreover there are industrial challenges. The energy transition requires the port to move towards a post-fossil industry and electrification of all landside and seaside activities. Finally, the port faces infrastructural challenges. Both the climate challenges and industrial challenges require the port to rethink its logistics and all transport between the port and the hinterland.

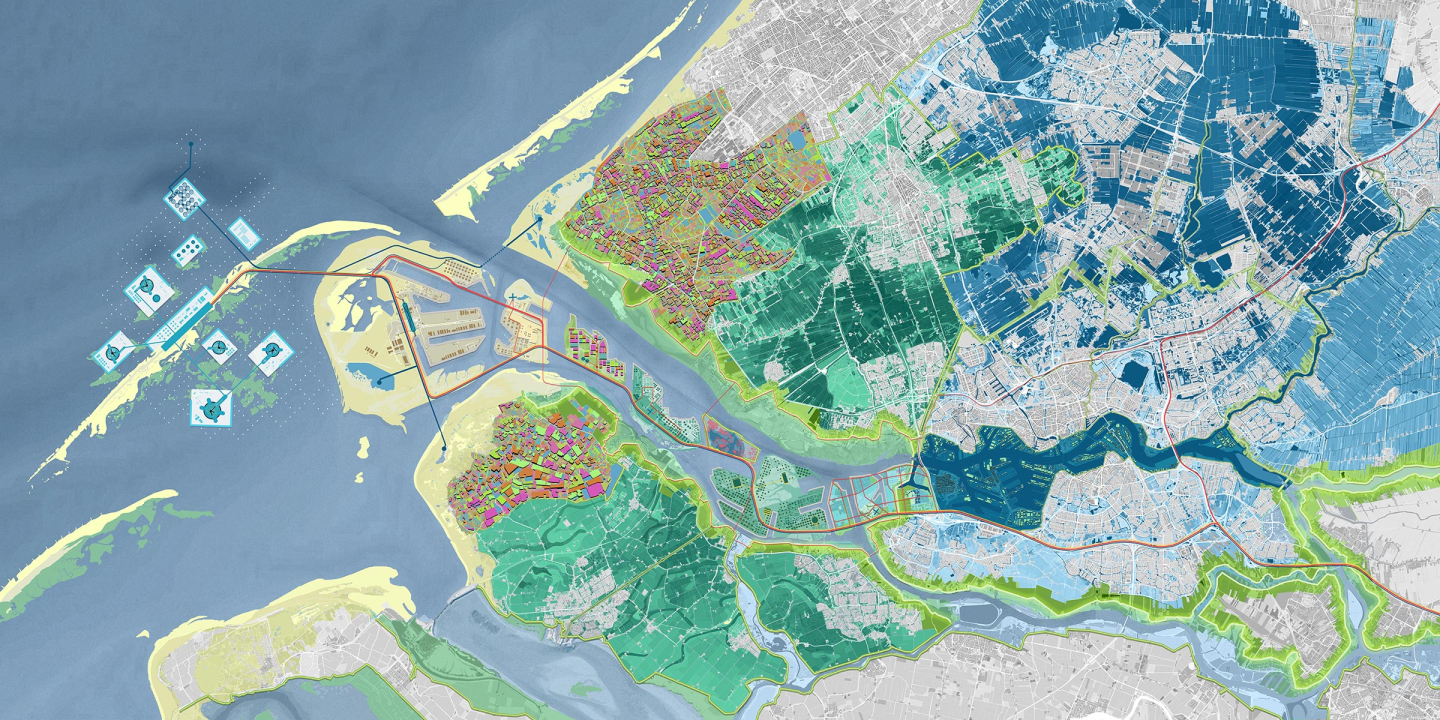

Before we propose any solutions or ideas, we first suggest to zoom out for a bit. Not to look at just only the port, but to see the port as part of an estuary landscape, with Dordrecht on one far end, and the North Sea on the other. Voorne-Putten and Hoeksche Waard, Krimpenerwaard and Alblasserwaard, Zuidplaspolder, Midden-Delfland and Westland are in a way all part of the port landscape. Not to forget the bustling city of Rotterdam. Any proposal for the future of the Port of Rotterdam should be see on this scale, or even larger. The scale of landscapes.

One dike, two locks, two strategies

The port of Rotterdam and the city of Rotterdam have always been inseparable, historically, spatially and mentally. However, the port has been moving out of Rotterdam decade by decade, separating itself gradually over time. The continued movement and separation of port and city is a big change: both the port and the city of Rotterdam could pursue different flood protection strategies to climate change and sea level rise. This allows the port to do the same.

We propose a new dike system in the Rotterdam region: a new route and layout for dike ring 14 including a replacement of the Maeslandtkering for a new lock at Pernis. Another lock could be built at Brienenoord. This allows the city of Rotterdam to have its own fresh water basin, much needed in a time where fresh water is becoming more and more scarce. Without the port, Rotterdam can become a Sponge City. At the port area, the new dike could be relocated inland, allowing more space for the estuary and its ecology. In this estuary, the port could transform into an archipelago of port islands in a natural estuary landscape. Let us explain.

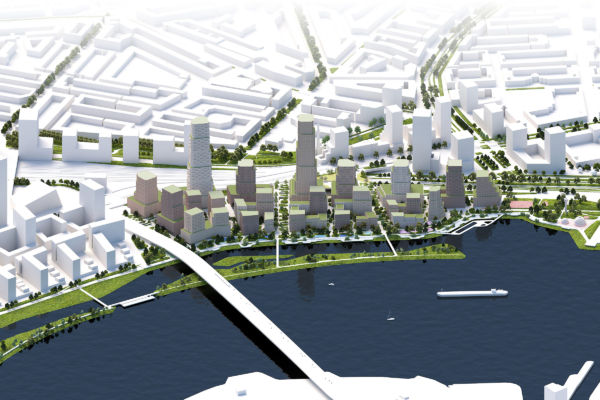

Port Archipelago

The Port of Rotterdam always has had a unique adaptation strategy. The post-war port areas were each raised several meters above sea level to ensure the safety of the ports and continued port activities. Every time a new port expansion was constructed, it was not only closer the North Sea, but also raised higher than the ones before. We propose to use this unique transformation strategy as a coping mechanism for climate change and sea level rise, ensuring the continued activities of the port as an important economy for Rotterdam, the Netherlands and Europe.

By having relative short contracts and short maintenance cycles, the existing and new port areas can adapt themselves gradually over 20-30-year renewal cycles to the sea level rise, the climate crisis, and the energy transition. We propose to develop the port areas during these renewal cycles step-by-step into islands, for this allows to create more space for biodiversity and natural processes. This way, the port becomes truly part of the estuary water system it is in and depends upon. The port could transform from an ecological dead zone into a natural steppingstone and safe haven for both land and marine ecology.

Port Archipelago adaptation strategy

Rotterdam Sponge City adaptation strategy

License to operate

This natural estuary is a fitting landscape for the port that wants and needs to transform from a polluting fossil-based industry, to a clean bio-based economy. This goes beyond the electrification of the port and its activities, but aims for the port to receive, store, and recycle renewable materials, such as woods, cellulose, etc. The port itself will still be noisy place with ‘a license to operate’, big ships and cranes, but with clean-tech and in a natural setting.

Not to forget about food, since food is a crucial part of the port economy. We propose to bring the production and trade of food into the port itself, creating a much stronger (and shorter) link between production, trade and transportation. In Westland and Voorne-Putten the will be a continued construction of greenhouses, while in the polders more extensive circular farming replaces monocultures and the intensive farming of cows and pigs.

Energy storage and production will transform from oils into a next generation energy: temporarily produced by wind mills and solar farms, future energy will nuclear, even produced in the port itself by local reactors. Boats, cranes, buildings, all will be electrically powered by commercially available nuclear fission. The benefits: clean energy and clean port: the air quality in and around the port will drastically improve. Not to mention the reduced emission of CO2.

Landscape connections

Landscape based port activities

In the end all these transitions don’t mean that huge areas of the port of Rotterdam will become available for uses other than port activities. Obsolete buildings and silos will just be replaces by newer, cleaner ones on a floodproof port island. Actually, even more space is needed. The North Sea, however also claimed for many other types of use, could provide the space for floating port islands. Perhaps these can even function as platforms for further space exploration.

Autonomous everything

Not only will the port change to adapt to the sea level rise, climate crises and new economies, also transport will change. Because the glaciers in the Alps are melting, and could have fully molten this century, the water levels in the Rhine, Waal and Meuse are dropping. The continued inland transportation of goods over water is unsure. An alternative is the railway, but it’s not suitable to the future port as there is relatively little technological development of the rails as a transport system for goods. The best option is automated autonomous transportation over roads. A new road system, dedicated for transporting goods, could be a solution, delivering goods from the port to the final mile and vice versa.

Rotterdam Sponge City

Energy Port and Food Port

Goods Port and Space Port